On Saturday 30 October 1886, the two greatest clubs of the nineteenth century met in Glasgow. This was more than just an Anglo-Scottish clash. Queen’s Park were the amateur purists against the new professional force that was Preston North End.

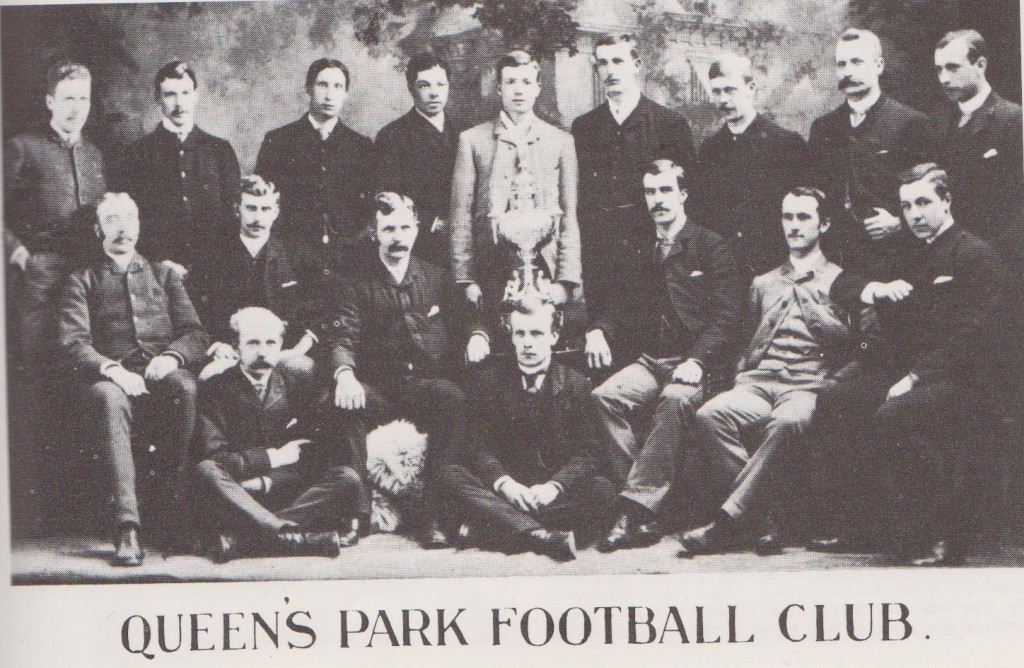

Founded in 1867, Queen’s Park was Scotland’s first Association Football Club. Previously football had been confined to the English aristocracy and Public Schools, but within a couple of years Queen’s had made the sport popular in Scotland, and indeed Ireland, as their tour of Belfast was directly responsible for the founding of the Irish F.A. Not only was the club responsible for spreading the game beyond England, it changed the very way in which football was played. Half time breaks, for example, were devised by the Glaswegians, before teams had swapped ends after each goal was scored, and there was no formal rest period.

In addition they also changed the style of football. Their players were pioneers of the passing game. This concept may seem straight forward to postmodern minds, but until the 1870’s players would dribble for as long as viable, only stopping when they were tackled by their opposite number. For the first decade of organised football, the sport was played in a manner akin to a playground encounter, as men crowded around the ball taking turns to try and get into a shooting position.

Another lateral concept was the purposeful heading of the ball. The F.A. rules simply stated that an outfield player could not use his hands; heading the ball was unmentioned. It was some time before people started to deliberately use their head to move the ball, and though Queen’s Park may not have been the very first to employ the tactic, they certainly honed their heading skills before any other major team.

In 1872, Queen’s Park was involved in two pivotal events in the evolution of football. It was the year that saw the climax of the maiden F.A. Cup, and the very first international fixture. It seems that the F.A. Cup was originally envisaged as a British-wide competition, and that is probably the reason why it was not christened the English Cup. As the only entrants from north of the border, Queen’s received a bye to the semi-final, where they played The Wanderers.

The former public schoolboys had expected a comfortable victory over their northern opponents, but were held to a nil-nil draw. The replay was never to be, as the Scots could not afford the train-fare for the long journey south, and had to scratch. However, Queen’s Park had impressed sufficiently for Charles Alcock, the most influential figure in the early days of English football, to suggest an England-Scotland match.

On St. Andrew’s Day of that year, the first international Football match took place at the West of Scotland Cricket Ground in Glasgow. The entire Scotland team was composed of Queen’s players, and as they donned their navy blue club jerseys, the strip was adopted as Scotland’s national colours from that day forth. The following year Queen’s changed their strip to black and white hoops, and have been known as The Spiders ever since. The match was a nil-nil draw, with the Scots better team work nullifying the individual talents of the English. It was not long before all the major English sides had adopted the Scottish ‘combination strategy’.

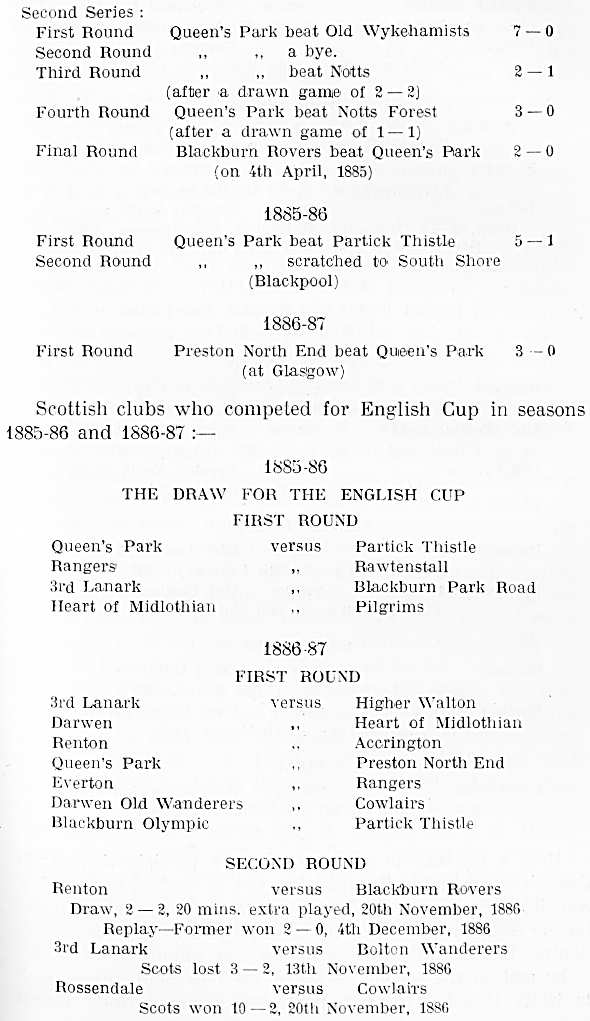

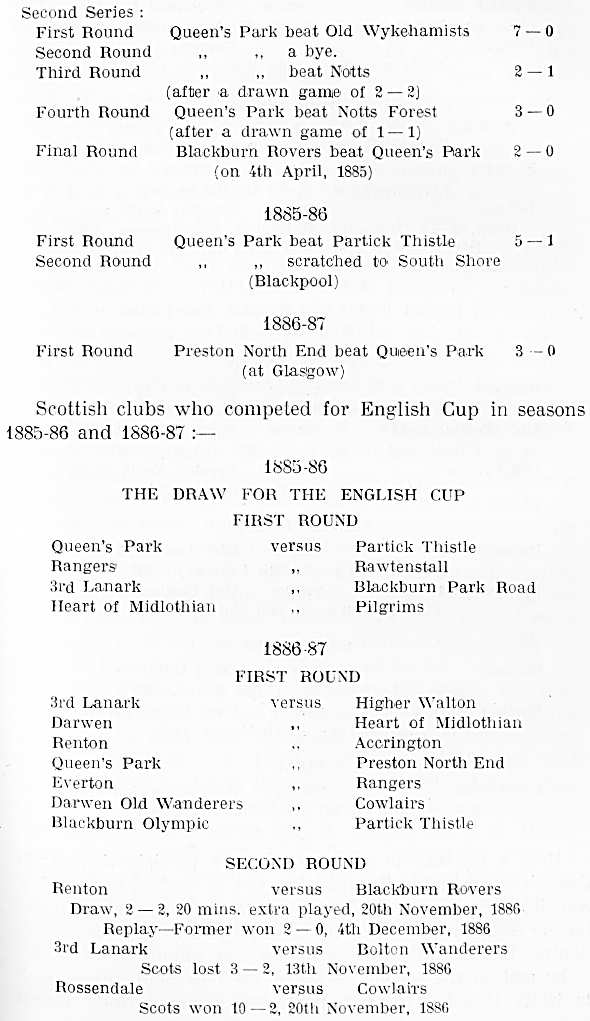

Two years later Queen’s Park would lift the first Scottish Cup, and would claim it a further nine times before the end of the century (to this day only Celtic and Rangers have won the title more often). By the 1880’s the club had managed to become more financially secure and could now afford to regularly compete in the F.A. Cup, twice reaching the final in 1884 and 1885, only to be vanquished by Blackburn Rovers on both occasions. Yet there was a slightly hollow ring to Blackburn’s victories, as one of the most feared teams in the country, Preston North End, was not present. The reason for this absence was the result of the most significant dispute in the history of Football, the debate on professionalism.

Just as Queen’s Park had transformed the amateur game and brought it to a wider audience, so Preston North End was embarking on its own revolution. Their leading agitator was William Suddell who did more than any other man to turn football into the professional sport that would conquer the World.

In the early 1880’s football had begun to take root in Lancashire towns such as Darwen, Bolton, Blackburn, and Preston. The Preston-born entrepreneur William Suddell had realised football’s huge potential early on, and began to surreptitiously pay his players. He acted as both chairman and manager, and was also prepared to travel in search of the most talented footballers of the age. In the 1880’s the finest were generally to be found in Scotland.

The Ross brothers were the best known Scots to be recruited. Jimmy Ross was a free-scoring centre-forward who would net seven goals in Preston’s record-breaking 26-0 demolition of hapless Hyde in the F.A. Cup. His older brother Nick was a defender with a fearsome shot who bagged dozens of goals in his career, and is also credited with being the first player to utilise the backpass to the keeper.

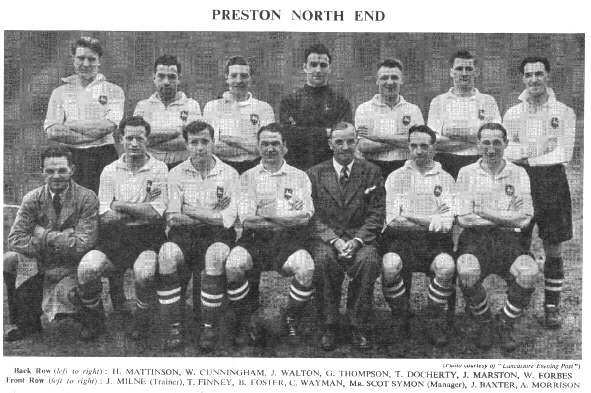

The 1953-54 Preston North End side

As Preston’s footballing reputation grew, so too did the resentment of their rivals, and North End were twice expelled from the Cup for paying players, something that was common place in Lancashire at the time. Suddell decided to take on the F.A. and instead of denying the accusations, admitted that the Deepdale outfit was amongst several practising professionalism. He then proposed a breakaway professional British football association. It was a row that nearly tore football apart, in a manner similar to the dispute that impeded the development of rugby. Eventually the F.A. had little choice but to relent, as a consequence Working Class men could now consider football as a career, and the sport never looked back.

When Preston was finally readmitted to the F.A. Cup in the 1886/87 season, their first round opponents were none other than the bastions of amateurism and Scottish Cup holders, Queen’s Park. The purpose-built venue was Hampden Park (now called Cathkin Park), a few miles from the famous present-day Hampden Park. Many football fans, even members of the Tartan Army, are unaware that Queen’s Park actually owns Hampden, and that the Scottish F.A. is merely a tenant.

That almost 20,000 Glaswegians, the majority of very modest means, paid to watch a sporting contest is in itself noteworthy, and proof that in the northern half of our island, football was becoming an antidote to the drudgery of industrialism. The hosts were determined to prove that an unpaid team could compete with a professional one, and there was also a sense of Scottish national pride being at stake.

The sport played that day was recognisable as football, though there were obvious differences with today’s game; the tackling was a lot rougher, there were no nets attached to the goals, the penalty kick had yet to be devised, and substitutions would not be introduced for a further eighty years. In truth the contest itself was unremarkable. North End cantered to a three goal lead and the Spiders never really looked in the match.

The partisan home support had been directing coarse comments at North End’s ‘turncoat’ Scottish contingency throughout the ninety minutes, but matters came to a head when Jimmy Ross fouled W. Harrower, sparking a pitch invasion. Ross was only saved from a beating by the intervention of Queen’s player Walter Arnott (who had guested for the Lilywhites a few weeks earlier). However the trouble did not end there, as the official Queen’s Park history records:

‘After the whistle blew, with Preston victors by 3-0, the enraged crowd broke in and demanded Ross junior, that they might wreak their vengeance on him. His life would have been in grave danger, were it not that the Queen’s Park officials successfully protected him, and spirited him away through a back window.’

Meanwhile the rest of the visitors were besieged in the changing tent by hundreds of baying fans, and it was some hours before the North Enders could sneak away. Even then the Queen’s Park fans were not pacified, and marched off to Glasgow Central Station in an attempt to intercept their quarry. The Railway authorities managed to convince the mob that Ross and his fellow players had been arrested, and were under custody in a police station on the south side of the city. Meanwhile the Preston party made good their escape from Glasgow. Amateurs Queen’s Park may have been, but there was little doubt about the fervor that football could arose amongst their supporters.

Passionate though their followers undoubtedly were, the sun was setting on the great era of Queen’s Park, and amateur football in general. The following year the S.F.A. banned Scotland’s sides from entering English competitions, and the club won their last Scottish Cup in 1893. At first The Spiders’ distaste for professionalism continued to influence football regionally.

In its infancy the Scottish league stayed amateur, and even then Queen’s refused to participate until the twentieth century. Additionally, players like the Ross brothers who ‘sold out’ to the English clubs were barred from appearing for the Scotland national team. Eventually however, as the Scottish international team lost its competitiveness, professionalism was permitted in Scotland. Queen’s Park however, remains amateur to this day.

Even the professionals of Lancashire would have to wait a further two seasons to finally achieve the glory Suddell and his lads so desired. At the end of the season West Bromwich Albion would upset Preston in the semis winning 1-0. North End came back even more strongly the following year dispatching all before them in a mammoth, and record-breaking, run of 42 consecutive wins. However Preston was again humbled in the Cup by unfancied West Brom, this time in the final.

Nevertheless, when success finally did come, it came in grand style. Not only did 1889 see PNE win the inaugural league season without losing a game, they then collected the F.A. Cup keeping a clean sheet for the entire campaign. The opponents in the Final were not West Brom (who Preston at last beat in the semis) but their Black Country archrivals Wolves. Preston claimed The Double with a three-nil victory. William Suddell had achieved the dream of turning his team into the greatest football club in the World.

Yet they would become victims of their own success. Professionalism began to work against small town teams. Clubs such as Everton, Aston Villa, Sunderland, Sheffield United, and later Newcastle, Liverpool and the Manchester sides were able to garner larger crowds due to their greater population, and hence could afford to outbid the likes of Preston and Blackburn in the pursuit of top players.

The contest between Queen’s Park and Preston North End symbolises the triumph of professionalism. Whether that was beneficial to football is a matter of opinion. William Suddell had hastened the, perhaps inevitable, advent of professional football, helping to transform it into the world’s most popular sport.

However, in the aftermath of that painful defeat over 125 years ago, maybe there were some Queen’s supporters who, wistfully remembering the club’s motto ‘ludere causa ludendi’ meaning ‘to play for the sake of playing’, wondered whether football really had progressed.

Written by Brian Heller

Like O-Posts on Facebook

You can also follow O-Posts on Twitter @OPosts